LE "GAINE"

Posso datare con precisione il mio primo incontro con la “GAINE” a ottanta anni fa; era la primavera del 1940 quando l’Italia entrò in guerra, un simile tragico evento non posso certo scordarlo anche se avevo appena compiuti i nove anni. Seppur sbarbatello mi piaceva ogni tanto recarmi nel magazzino di attrezzature di cucina di nonno Pasquale e di mio babbo Giannino, situato in via San Pietro all’Orto, conosciuta via traversa di destra del centralissimo corso Vittorio Emanuele di Milano.

Nel magazzino Medagliani si accedeva attraverso un cortile ottocentesco acciottolato. Il primo locale d’ingresso costituiva il negozio di vendita al pubblico, seguiva il laboratorio di affilatura coltelli, poi l’officina di lattoniere del nonno ed infine il magazzino si completava con la sartoria condotta da nonna Caterina che con alcune giovani sarte confezionava indumenti di lavoro per cuochi ed anche la famosa “toque” copricapo simbolo della professione d’arte di cuoco.

Il locale che più mi affascinava era evidentemente il locale di nonno Pasquale, grazie alle curiose, semplici ed un poco misteriose macchinette manuali, utili a tagliare, piegare ed arrotondare i bordi di lamiere di latta, di rame ed ottone, grazie alla loro efficienza e soprattutto all’abilità manuale e creativa del nonno venivano approntati stampi per dolci, paté in crosta, tagliaverdure e tagliapasta oggetti che ancora conservo con orgoglio nel magazzino in alcune vetrine espositive ricche di antichi utensili dell’arte culinaria!

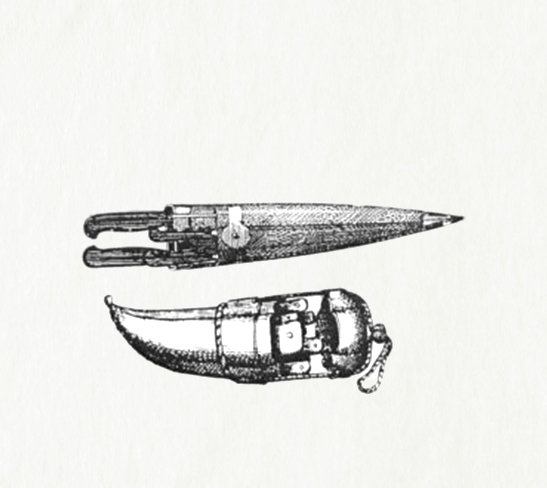

Fu proprio il nonno a presentarmi due pregevoli ed eleganti guaine vedi (fig.1-2) una di cuoio conciato, l’altra di legno di noce, fabbricate da abili artigiani ed alle quali lui stesso collaborato con l’inserto di parti metalliche. Più o meno lunga la gaine disponeva da cinque a sette scomparti . Il puntale e le fasce metalliche che le guarnivano erano di alpacca argentata, ageminate ed istoriate. Sul liscio bottone metallico inserito per facilitare l’aggancio della Gaine ad un foro praticato nella cintura dei pantaloni, si sarebbero poi incise le sigle del nome del proprietario.

La Gaine si completava con l’inserimento dei ferri da taglio indispensabili allo chef di cucina, di un affilacoltelli, un forchettone a due denti e qualche ago per lardare e cucire.

Finita la guerra, ridimensionatesi le brigate di cucina, dimenticato il prestigio dei grandi Palaces, anche le Gaine sono sparite insieme ai grandi cuochi fedeli esecutori della Grande Cuisine.

Oggi le Gaine sono ormai diventate costosi oggetti di antiquariato.

Affinché i giovani cuochi possano osservare come questo oggetto sia simbolo di comando e di professionalità per almeno sei secoli, vi propongo alcune antiche incisioni di cuochi e delle loro Gaines.

Nell’OPERA di Bartolomeo Scappi, seconda metà del 1500 nella pagina dei “diversi coltelli”

(Fig. 1 – 2 ) è raffigurata una guaina che lo Scappi chiama “ coltellera

(Fig. 3 -4 ) nelle incisioni del “Von allen Speisen und gerichte”( 1530) si vede una guaina infilzata nella cintura di due cuochi.

(fig. 5 – 6 ) nei testi di cucina del 18° e 19° secolo molte sono le illustrazioni di cuochi con la Guaina, tanto che in alcune di esse sembra proprio che il cuoco voglia evidenziare grazie alla guaina il l grado professionale raggiunto – non semplicemente cuoco ma “chef de cuisine.”