Pensiamo ai tre utensili sempre presenti sulle nostre tavole: forchetta, cucchiaio e coltello.

Oggi vi parlo dei primi due:

Il Cucchiaio

Se penso all’origine del cucchiaio, mi piace immaginare Eva mentre si disseta, appoggiando le labbra ad una conchiglia di madreperla. Infatti il primo oggetto adatto a raccogliere e a contenere un liquido potrebbe proprio risultare essere una foglia o un guscio di tartaruga. Il suo nome latino cochlear: conchiglia, ci assicura sulla sua origine.

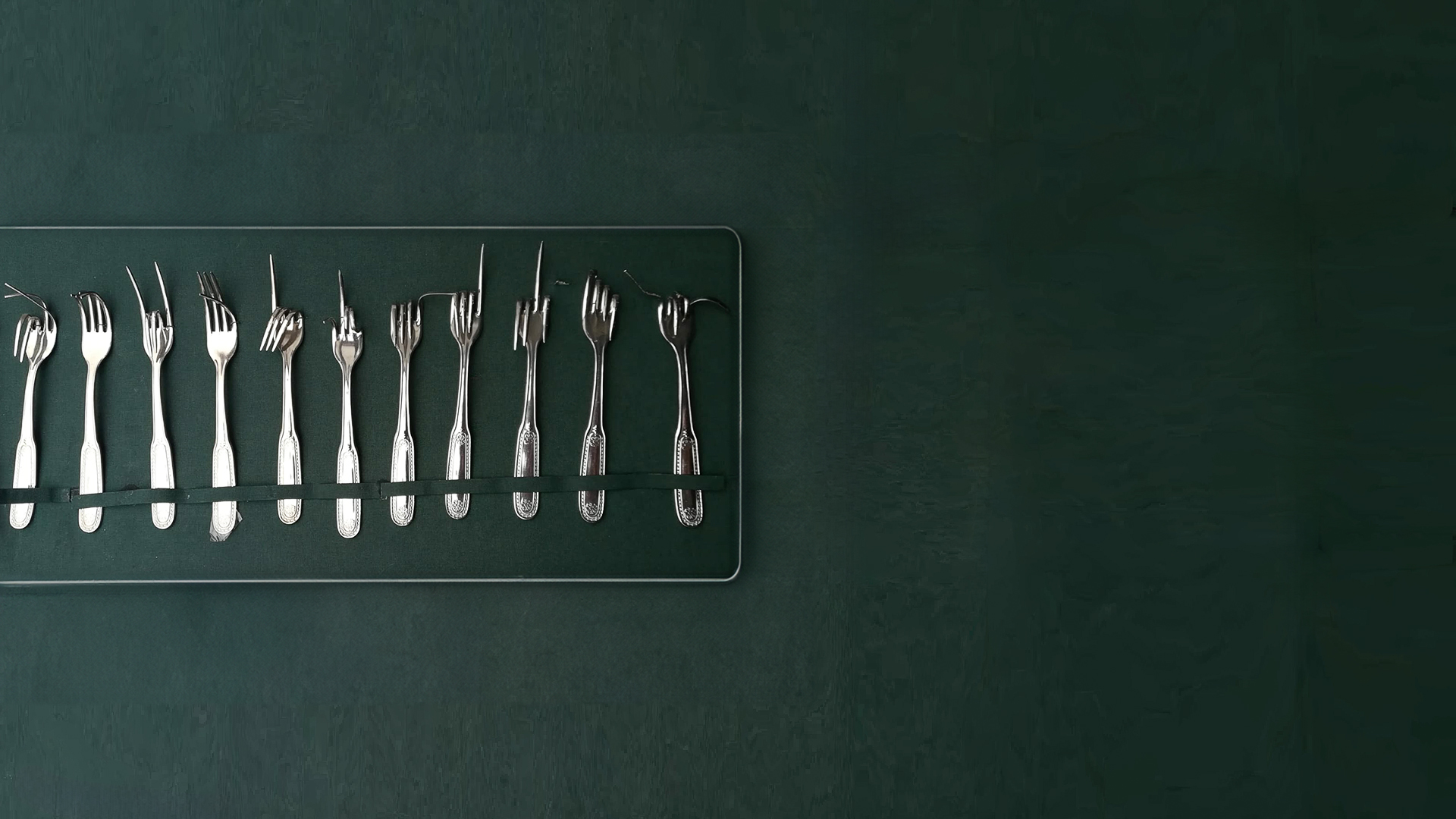

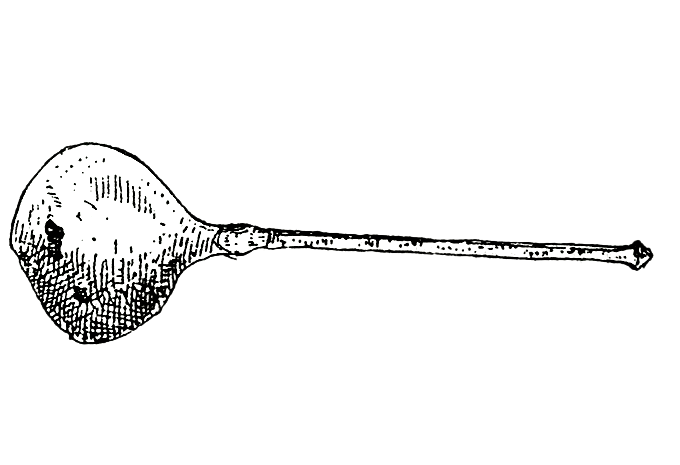

Il cucchiaio non ebbe presso la mensa dei romani un uso molto esteso, infatti venne utilizzato molto raramente e talvolta in sostituzione della forchetta. Giova ricordare che allora i cibi venivano presentati ai commensali in piccoli pezzi. I cucchiai di epoca romana erano simili a piccoli mestoli con un manico a punta Figura 01.

Pare che a quei tempi i cucchiai fossero utilizzati per mangiare le uova mentre la punta del manico risultava assai utile per estrarre molluschi e lumache dal loro guscio. La coppa del metallo, rimasta invariata per secoli, è mutata nel 1700 quando, per adeguarsi alle nuove norme del galateo, cambiò il modo di impugnare il cucchiaio che non fu più chiuso nel cavo della mano ma afferrato tra pollice ed indice e sostenuto col dito medio.

La forchetta

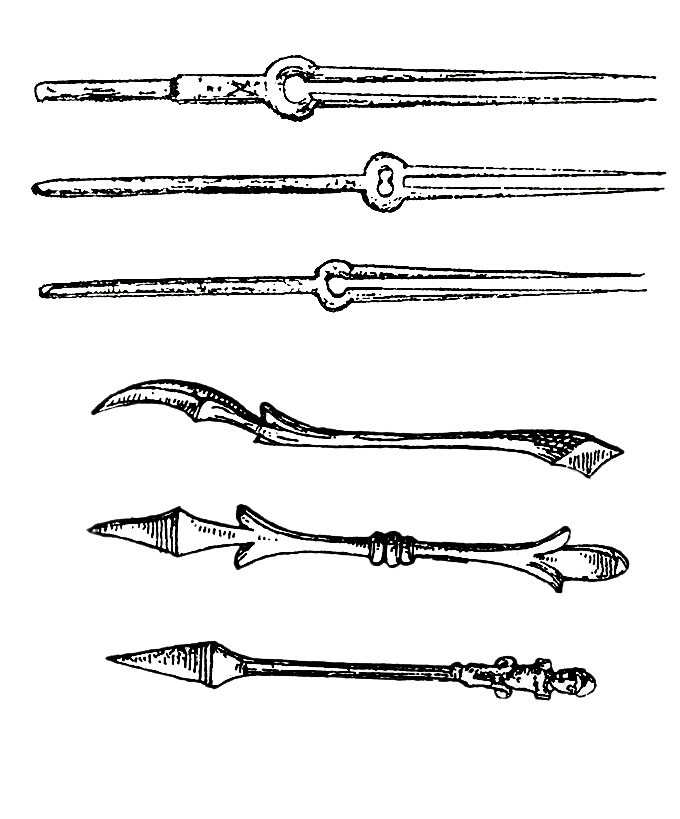

La necessità della forchetta fu certamente meno senitita, perché la natura ha dato all’uomo la forchetta d’Adamo, cioè le dita, adatte ad afferrare facilmente qualsiasi oggetto o alimento. Nacque così per ultima e il suo sviluppo fu molto più lento. Venne, solo sporadicamente, utilizzata per scopi conviviali, restando per lo più relegata in cucina sotto forma di quel grosso forcone che i cuochi utilizzano per togliere dai caldari i grossi pezzi di carne e che gli scalchi impiegano in sala per immobilizzarli ed affettarli Figura 02.

L’origine della forchetta risale certamente ad epoca molto antica, non facile a stabilirsi, ma il suo impiego in Italia non risale a molti secoli addietro. Questo oggetto da tavola fu dimenticato dagli scrittori nella descrizione degli antichi conviti e lo trascurarono anche i pittori, ma fu presente negli inventari delle masserizie domestiche, dove compare col nome di imbroccatoio, broccatoio e brocchettoFigura 03 che deriva dal verbo imbroccare che significa oltre che cogliere nel segno anche infilzare, come parrebbe la sua etimologia derivata dal francese broche, che in italiano significa spiedo.

è tra l’VIII e il X secolo che la forchetta, come noi la intendiamo ed utilizziamo, trova collocazione sulle raffinatissime tavole di Bisanzio, favolosa capitale dell’Impero Romano d’Oriente, da cui viene portata in Italia allorchè la principessa bizantina Maria, andata in sposa al Doge Orseolo II recò in dote una forchetta d’oro a tre rebbi, la nuova usanza di prendere il cibo con una forchetta invece che con le mani, tanto scandalizzò il frate Pier Damiani da supplicare il Papa a mettere all’indice la forchetta perché simile all’utensile (il forcone) maneggiato dal diavolo.

Ma venuto il secolo delle accademie e delle parrucche, la forchetta fu l’oggetto che sembrava meglio rispondere alle ricercatezze e al manierismo più effemminato, da allora anche la forchetta, di cui tante generazioni ne avevano fatto meno, incontrò il favore generale e si rese indispensabile su ogni mensa.

Eugenio Medagliani